So, you've cut off your breast(s) and poisoned and radiated your body. You've hit all your medical milestones - surgery, chemo, herceptin. You've recovered and the hair on your legs has grown back to plague you, and you have gotten back to a normal life. Work, jobs, family.

Shaving.

Yet you are changed. You didn't expect this, but each time you get dressed or undressed, you can't help but notice your mastectomy scar is smiling at you. Each time you unscrew a jar, you feel your muscles jump in weird ways and you are reminded that you are different. You know now that you can never forget; cancer can't be swept under the rug with the detritus of your other medical memories, like cramps or a post-childbirth hemorrhoid.

Cancer is always in your mind, if not in your body. Not to the level it was when you were first diagnosed, or when undergoing treatment. But, it is a part of you now, a part of who you are. Why is that? What is it about this disease that is so different than others, that it becomes a part of your identity? Is it only the physical changes, or something else?

I had migraines for 25 years. Bad ones, that left me quaking in agony in a darkened room, moving only to vomit. Those migraines changed my life more than cancer did - were more debilitating. I had them several times a week. I couldn't leave the house, go on vacation, go on a date, raise my child, without making sure I had enough meds to make it through. Yet, I don't consider them a part of my identity.

Not so with cancer.

I have migraines, I am a cancer patient.

I suppose the treatment can help explain it - it can be quite intensive. It's hard and so you have all these milestones that you check off - it's an all-encompassing part of your life for well over a year. The only thing that compares in time consumed is being the mother of a small, colicky infant, and even that ends in six months.

That treatment can be intensive doesn't explain why people with small stage I cancers whose entire course of treatment is mere weeks feels exactly the same about it as a Stage III woman does.

I suppose the place cancer has in our culture plays a role. We have months dedicated to the disease, constant fundraisers, commercials all day long about cancer centers, preventative methods - it's pervasive. "The Cure for Cancer" has been a medical goal for researchers for decades and movies are regularly made about a brave cancer patient "battling" her disease. Cancer has a place in our collective experience that other diseases don't, and we are the anointed ones. All of those never-ending commercials and fund-raisers - it's about us.

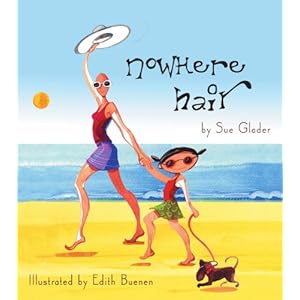

Also, we can't keep it a secret, like those with high blood pressure can. We don't get to face our disease in private: we lose our hair and are thus outed as cancer patients. If we leave the house, we tell the world.

It's also true that the fact that the disease can come back and strike at any time is part of the reason it never fully leaves your psyche. There is still no good way of telling who will face it again and who will be cured, and I would have paid $1,000 if they had that circulating tumor cell test available when I was first diagnosed. But, they didn't, and as they say, you only know if you are cured from invasive breast cancer when you die of something else.

So, you end up in a peculiar no-man's land for a while. You have to accept the fact that you may face this disease again, while at the same time, living your life as if you won't.

You probably won't. The odds are good.

But, you might.

And so, to know the unknowable, we cling to numbers most of us can't even understand. The lore is: in five years, your risk for recurrence drops dramatically. For us HER2+ gals, we recur in three years because our cancers are so aggressive. After the third year is up, our chances go down to the same as anybody else. After five years, we rarely face a recurrence. (Except for the exceptions - I know a woman who faced a recurrence 22 years after initial diagnosis, and isn't that a slap in the face?) Confusing the matter - herceptin hasn't been around for a long time so nobody really knows if we will start to recur down the road or not, or what exactly, it does long-term for early stagers.

But, since it's all we have, we go by the three year stat - why not?

From when do they start counting? Each oncologist seems to have a different start time. Some say the clock starts ticking on the day of diagnosis. Others, from the day of your mastectomy. Or, it starts from the day of your last chemo. It starts from the day of your last herceptin. I suppose that it all depends on what study they are going by.

I forgot to ask mine what he thought, damn chemo brain. It makes sense that it would start from last treatment date but things in the medical world involving statistics rarely make sense to us mathematically-challenged commoners.

So, here I am on the Three Year Danger Zone continuum.

Diagnosis August 2009: Enter safe zone August 2012. Only 18 more months!

Mastectomy October 2009: Enter safe zone October 2012. Only 20 more months!

Ended Chemo March 31, 2010: Enter safe zone March 31, 2113. 2 years, 1 month.

Ended Herceptin December 2, 2010. Enter safe zone December 2nd, 2013. Still 2 years, 9 months to

Clearly, I'm rooting for the definitive answer to be from the date of diagnosis. In 18 months, will I be able to take a big sigh of relief and call myself a Survivor?

I think I'll have cake on each one of these dates, just in case.

Mmm....cake.

.